RUBY

|

RUBY |

|

|

|

|

NAME: Ruby COUNTY: Santa Cruz ROADS: 2WD LEGAL INFO: T23SN, R11E CLIMATE: Mild winter, warm summer BEST TIME TO VISIT: Anytime |

COMMENTS:

One of the best preserved ghost

towns in Arizona. To gain access you must help in the restoration,

hour for hour. Video available, see below. REMAINS: Most all the buildings are left standing. |

|

Ruby's post office was established April 11, 1912 and was discontinued May 31, 1941. Ruby is one of the best preserved ghost towns in Arizona. It is now undergoing restoration and you can visit the site if you help in the restoration. For each day of work you get a day of play. For forty years Ruby was called Montana Camp and in 1909 was changed to Ruby in honor of one Julius Andrew's wife. Julius Andrews was in charge of the camp store and was the one who applied for the post office. At one time over 150 children went to school in Ruby and over 300 men were employed at the Montana Mine.1941 saw the end of operations at Ruby and it has been a ghost town since. For more infomation on Ruby from Tom McCurnin, click here. For a current map of Ruby click here. For a map of the Montana Mine, click here. To see the Ruby Brochure, click here. - GT Ruby (Montana Camp) is 25 mile to the west after Pe�a Blanca junction on SR 289. Possible to drive in 2 WD with careful driving. Ruby is one of the leading ghost towns in the country, passed only by Vulture who had more standing buildings. Ruby is total closed for visitors. Mining in the area below Montana Peak began first in 1870 (eighties) and town who grow up around became known as a Montana Camp. Owner of the general store, Julius Andrews give the city his name when the post office was established on April 11, 1912. He named the post office (and with this the city) after his wife, Lillie B. Ruby Andrews. Philip C. Clarke bayed Andrews general store in 1913 and build one bigger on the hill, were is still standing. Because the area were close to the Mexican border and attacks were almost daily, Clarke and his wife Gypsy had a weapons in every room of the house and store. Their son Dan, one popular Arizona man who died in 1922 told that his father send the mother to California to born a baby because the situation in Ruby were dangerous. In the times when all ranchers were attacked from the Mexican revolutionaries who crossed the border, once Clark were asked by a older man with name Guzman, what was that pipe looking apparaturess on front of his house? Clarke who loved to joking with the old and serious man, told him that was a pipe system witch made him possible (or: made him able) with a bottom beside his bed to let out the poisoned gas, and that gas were strong enough to kill one all regiment. Clarke enjoyed to see the old men walking far around from pipes, witch actually were pipes for the rein water. When Guzman returned one month later, Clarke asked him did he seen some revolutionary soldiers: -"Oh, yes..... The checked everything I had with me, but they only took my tobacco from me". Clarke asked him did they say they want to come to Ruby store and Guzman answered: -"Yes, they asked Me about everything and I tell them about your dead machinery - those pipes with the poison gas". Solders decided to avoid the Ruby store. After this Clarke say: -"I was much careful to talking about my dead spreading machine". Others were not so lucky. Clarke leased the store to Alex and John Frasier in 1920 and suggested them to be good armed. Les then two months later lied Alex dead beside cash register and John was shoot in one eye after he were forced to open the store's safe. John lived only 5 hours more. One of the two rowers were later killed when he refused to be arrested, but he were able to kill the deputy, and the another robber was never found. Clarke filed guilt for destiny of the Frasier brothers when Frank Phearson came to buy the store. Phearson was sure that the lawless was not so big and that attack was not possible. He became the next store owner and on august 26, 1921 were him self and his wife killed by 7 armed man. Their youngest daughter Margaret failed down when she tried to escape and when she looked up, the butcher (killer) stand over her, and with non known reason, he turned around and walked back in the store. Margaret Phearson Anderson which survived became teacher in Nogales and Tucson, and retired in 1980. Two of the 7 bandits were recognized when they escaped from Ruby. Placido Silvas and Manuel Martinez were arrested, brought to the court, convicted and send to be hanged. The Sheriffs car witch drive them to the jail in Florence tipped over, killed the Sheriff and wounded the deputy, and the prisoners escaped. Martinez were later captured and hanged in the Florence jail. Silvas were never found and that's possible hi is still in live today. The flourishing time in Ruby began in 1926 when Eagle-Picher Lead Company over-take the mining. The town had a electricity (made by diesel machines), doctor, hospital and one school with 3 teacher. Once were over 150 children witch joined the school. >From 1934 until 1937, Montana mine was a leading producer of lead and zinc in Arizona, and in 1936 was the third biggest in production of silver. The mine employed over 300 men, but ore died in 1940 and the town witch once had about 2000 citizens, became ghost town in 1941. Post office closed on may 31, 1941. Clarke's store which were intact until 1970, collapsed totally, but the jail not far from there is still standing. The school still standing with the basketball plate. On the south side of the city are mine offices and owners residence. Another buildings are visible from the road, from the little hill. Don't go in on the area without permission! Bobby Zlatevski

How We Trapped the Deadly Border Bandits By Oliver Parmer As Told To Kathleen O’Donnell From Startling Detective Magazine; March 1936

As early dusk of February 27, 1920 settled over the deserted town of Ruby, Arizona, a Mexican ranch hand shivered and pulled his frayed mackinaw closer about him as he trotted past boarded-up houses, to a forlorn building of adobe and weathered wood. The ramshackle building, a relic of better days when the copper and silver mines of Ruby were working, now housed the post office, general store, and home of the brothers, John and Alexander Fraser, who eked out a precarious existence serving the needs of the meager population of the once prosperous Oro Blanco mining district. The Mexican dismounted on the dusty street and tied his horse to a rail. A chill wind howled eerily through the mouldering desert town as he tried the heavy door. Finding it locked, he pounded. A shutter banged disconsolately somewhere nearby. Receiving no answer he knocked again. The echo was his only response. “The boys must have gone to Nogales for the day,” he muttered to himself. Stepping to a window, he cupped his hands about his eyes and peered in through the failing light. “Madre de Dios!” he exclaimed for he could discern that the safe was wide open and its contents scattered. Without further investigation he leaped on his horse and galloped to the ranch of John Maloney, justice of the peace. He panted out his story. John Maloney, a stalwart old Indian fighter and peace officer who had yet to meet his match for courage, strapped on his .45 Colt, grabbed his Stetson, and called in his vaqueros. “Vamos! Let’s go,” he cried. “The post office has been robbed!” Later Maloney and his men pulled up their laboring horses in front of the building and walked briskly to the door. Lanterns were being lit when suddenly, almost like an echo, a low moan, faint but unmistakable, emanated from the building. A sensation of horror swept over the group. “My God, what was that?” Maloney asked grimly. One of the vaqueros crossed himself and murmured a prayer. The cry came again, this time lower and long drawn out. Scarcely audible, it seemed inhuman. “Quick! Break in the door,” ordered Maloney, drawing his gun. The men complied and, stepping over the broken door with lanterns held high, they glanced around the room. Sure enough there was the yawning safe. Maloney gasped and his face blanched for by the counter laid the crumpled form of Alexander Fraser. An agonized moan drew their attention to the doorway leading to the living quarters. There lay the tortured body of John Fraser, his life’s blood oozing from a ghastly head wound. Beads of perspiration glistened on Maloney’s forehead. This was no suicide pact, no accidental shooting. It was plain robbery and murder. The telephone, the only one in Ruby, had been torn off the wall and its wires cut. “Gutierrez, take my horse and ride hard to Nogales. Get Sheriff Earhart and an ambulance.” At this time there were no autos in Ruby. Nogales, forty miles away, was the nearest town.

Double Tragedy So it was that in the early hours of dawn I was drawn into the investigation by Sheriff Ray B. Earhart, for I was the Arizona Ranger in the Oro Blanco district. With three deputies we drove to Ruby as fast as road conditions permitted. Although we were prepared for the sight of death we were appalled at the grisly scene within the post office. Alexander was dead. A bullet had entered his back, coursing to the front, and a second had penetrated his head. This unquestionably had caused instant death. John had been shot through the left eye and the bullet had passed through his skull. He was still alive but unconscious. We placed him in the ambulance and sent him to a Nogales hospital. He was our one hope of learning just what had happened. But our hopes in this direction were blasted when he died en route to the hospital without regaining consciousness. It was evident to us that more than one man was responsible for these murders for Alexander had been shot twice and by weapons of different caliber. The absence of powder marks on the clothing and skin of the victims indicated that the fatal bullets had been fired from a distance. Gunplay was not uncommon in Arizona where, due perhaps to the lingering spirit of the Old West, men often faced each other and shot it out. But this was different. Alexander Fraser had been shot in the back in cold blood after he evidently had complied with the demands of the killers by opening the safe. As to the characters of the Fraser brothers I learned much from Justice Maloney and others whom I questioned later. They had lived in Ruby for a number of years, were unobtrusive, well liked, and had no known enemies. They were especially kind to the Mexican peons in the district, often extending them credit for food. Seldom, indeed, had a crime seemed more cold-blooded. Was there something in these men’s past that brought on this killing? Was there some document hidden in the safe? Did the Frasers recognize the intruders and were the Frasers killed to prevent identification? “There’s a curse on that building” one old timer told me. “How’s that, Dad?” I questioned. “Old Tio Pedro died years ago. He predicted evil for the occupants of the post office ‘cause it was built over an old padre’s grave.” From Maloney I learned that the Tio Pedro superstition was common among the poorer Mexicans. I made a close examination of the premises for clues but found nothing tangible. Beans in a pot on the stove were charred and a pan of biscuits in the oven were burned black showing that the Frasers were in the act of preparing their evening meal when they were interrupted and struck down. The clang of the school bell within a stone’s throw of the post office suggested a possible source of information. I went to the school and had a chat with the teacher. “On my way home at about four o’clock,” she said, “I passed two strange Mexican vaqueros eating apples at the old adobe ruins just above the post office.” “What did they look like?” I asked eagerly. “They were typical vaqueros. One had a long drooping black mustache, the other a heavy beard. Their horses were grazing over in back of the ruins.”

Clue of the Cigarettes With this as a lead, Maloney and I hurried over to the ruins in search of clues. We found two sets of fresh footprints in the dust, the deep heel marks indicating that they had been made by men wearing the customary high-heeled cowboy boats. In a corner we found three apple cores and five cigarette butts. A curious thing about two of the cigarette butts was that the smoker, in putting them out, had broken the end off between his thumb and two fingers. Back at the post office I found another of these broken cigarettes and also a box of apples which indicated that the strange Mexicans had visited the store prior to the murders. The shooting had not taken place before four o’clock because the teacher and her pupils declared they had heard no gun reports during the day. We were unable to gain further information about the vaqueros as no one else had seen them. Late that afternoon a prominent rancher of the Oro Blanco district reported that two of his best saddle horses and eight head of cattle had been stolen during the night. Thinking there might be some connection between the murders and the cattle rustling we drove over to this ranch. We obtained horses for our posse and, picking up the cattle rustlers’ trail, trotted out into the barren wilderness after them. The fugitives were traveling fast, driving the cattle before them, confident that they could cross the border at some deserted point and be safe in Old Mexico by daylight. At this time Mexico was not recognized by the United States and consequently there was no treaty of extradition in effect, so that once across the border a criminal was perfectly safe. Although we were two days behind the bandits we kept on in the hope that they had been delayed in their efforts to smuggle the rustled cattle across the line. The following morning deputy sheriffs and civilians from Pima, Cochise, and Santa Cruz counties, armed with the descriptions of the stolen stock, searched mountain gorges and hidden gulches of the Oro Blanco district while the immigration officers and U. S. troops from Nogales patrolled the border. Our posses rode over tiresome hills veined with ore bodies of great richness, across dry washes flecked with gold, a land of vast distances, beauty, wealth, and opportunity where Spaniards of Coronado’s day marched over from Mexico in quest of the fabulous seven cities of Cibola. We did not get sight of the rustlers.

In the months that followed the investigation went on with Sheriff Earhart flooding the country with circulars describing the pod office killings. Many suspects were rounded up by able officers, but no charges were made. Cattle rustling continued in the Oro Blanco district and an occasional Mexican bullet whined across the line.

A New Postmaster A Year later found the Ruby post office in charge of young Frank Pearson, a native of Texas. Pearson was married and the father of a pretty four-year-old girl, Margaret. He purchased the stock in the store from the Fraser heirs and was assisted in his duties by his wife, Myrtle. That year, 1921, the rains were few and water holes dried. Hundreds of cattle died because of the drought. The Pearson’s grew lonely for even John Maloney went away for the summer leaving them eight miles from a habitated house. So Mrs. Pearson sent for her younger sister, Elizabeth Purcell, and also her husband’s sister, Irene. It was the first time the two girls had been away from their homes. The girls helped Myrtle Pearson with the household tasks and she and her husband had more time to ride out over the brown hills. The morning of August 26 gave promise of another stifling day in the post office. The Pearson’s had their breakfast at seven o’clock and at eight Pearson opened the office as was his custom. Shortly thereafter, leaving the girls in charge, the couple mounted their ponies and rode out over the surrounding hills. From Ruby Mountain they looked down toward Mexico, the land of manana, of romance, and of other, more sinister, things when suddenly Pearson’s horse picked up his ears and braced his forelegs stiffly. Down below on the trail several vaqueros were galloping toward the post office. Pearson’s face beamed. ‘There is going to be business in the store and the girls may need us” “I’ll race you back,” Myrtle cried, spurring her horse. They raced across the mesa in the balmy morning air avoiding clumps of cactus and scrub oak. They reached home breathless and radiant, with flushed faces. The vaqueros were leaving as they drew up. Myrtle and her sister retired to the living quarters with little Margaret Irene began straightening the shelves; Pearson was sweeping the floor. The door opened. Two vaqueros reentered the store and strode to the counter. “Tobacco,” they ordered. As Pearson turned his back to reach for the tobacco the Mexicans exchanged significant glances. The next instant two guns roared. Irene screamed. Pearson staggered, drew his gun from under the counter and fired three wild shots at his assailants. Then death stilled his trigger finger. The killer with the drooping black mustache, leering evilly at Irene, waved his smoking gun at his companion and ordered him to get all the “gringo’s dinero” (money)

A Second Murder Screaming at the top of her voice, Irene ran back into the rear of the building. The bandit pursued her, waving his pistol wildly. The blood froze in her veins. She stumbled. He caught her, grabbed her by the hair and dragged her across the room. “Stop! For God’s sake, stop!” Myrtle shrieked running into the room. The mustachioed one glanced up and avidly appraising Myrtle’s trim matronly figure roughly flung Irene aside. Then something else attracted him as Myrtle Pearson opened her mouth and screamed - the glint of five gold-crowned teeth! He sprang up, clutched her arms fiercely and brought the muzzle of his .45 down hard on her head. She collapsed, groaning. The killer stood up, as if enjoying the situation, and aimed at her helpless body writhing in agony on the floor. Bang! Blood spurted from a wound in her neck. The fiend jerked her head around by the hair and, forcing her mouth open, calmly knocked out the gold crowns with the butt of his gun! While this mutilation was taking place little Margaret appeared in the doorway, her eyes wide with stark terror. Irene grabbed her before she could betray her presence. Together they rolled under a couch, where they remained unnoticed. Elizabeth in the meantime crawled behind the counter and obtained Pearson’s shotgun. But the mustachioed one was quick as a cat. There was another flash from his gun! An agonized scream! The shotgun clattered to the floor and Elizabeth slumped behind the counter. The killer seeing the bleeding and mutilated form of Myrtle Pearson twitching in agony on the floor bent over her. There was another roar. Her body stiffened, the twitching stopped. The bandits shot open the sale and went through its contents. Money, stamps, post office money orders were pocketed. They helped themselves to all groceries they could carry from the store’s shelves. They tore the telephone from the wall and walked out into the corral where they stampeded the Pearson’s horses by beating them with sombreros, howling like coyotes and firing their pistols. Jumping on their horses they were off. The echo of racing hoofs beat back and forth through the hills with taunting madness to the girls left in the house. Irene and little Margaret crawled from beneath the couch uninjured. Irene revived Elizabeth who had fainted. Her arm was bleeding where a bullet had grazed it. Frank and Myrtle Pearson were dead. The girls surveyed the shambles. They cried, dried their eyes and cried some more. With the telephone wires cut, the horses turned out, there was no way of summoning aid. Business was so quiet it might be days before some passerby came along. The two girls, still in their teens, and little Margaret suddenly were faced with heavy responsibilities. They couldn’t stay where they were, with the dead eyes of their loved ones staring at them.

Summon Aid Weeping and hysterical, the girls stumbled over a dusty desert trail in blazing heat of noonday to the ranch of their nearest neighbor eight miles away. “The Ruby post office has been robbed and the postmaster and his wife murdered in cold blood,” was the word brought to Nogales that afternoon. With Sheriff George White, successor to Earhart, and three deputies I arrived at the scene of the crime just as the sun was sinking behind the topmost peaks of the Ruby Mountains. Chairs were overturned in the store, drawers were pulled out, papers scattered, the safe rifled, blood spattered on the floor, and boxes, bottles and canned goods strewn about. Pearson lay behind the counter in a pool of blood with two bullets in his back - stiff in death. His wife’s lifeless body lay sprawled on the floor. Her skull was fractured, a bullet had entered her neck and ranged downward, another had entered her left temple and come out at the back of the head, her jaw was broken, her lips horribly mashed and lacerated. Many of her teeth had been knocked out but they were not on the premises. I turned from this shocking sight resolved to do my utmost to bring to justice the fiends responsible for this mutilating atrocity. White’s lips were set in a thin hard line, his face was pale with fury and I knew that he was as determined as I. He knew what I was thinking - Pearson shot in the back like Alexander Fraser and almost on the same spot where the latter had expired some eighteen months previously. The safe open, its contents scattered, the telephone torn from the wall as before. Were the same persons responsible for both double murders? Was robbery the motive? It seemed that old Tio Pedro’s legend was still working. A quick search of the building revealed nothing further so I rode through somber scatterings of mesquite beneath a blanket of brilliant desert stars to the ranch house where the girls had taken refuge. I wanted to know what light they could throw on the case. They related the grim details of the murders. Their descriptions of the killers checked with that of the men the school teacher had seen on the afternoon of the Fraser killings.

Posses Take the Trail News of this latest atrocity at the Ruby post office spread rapidly through the Oro Blanco district. Peons in the vicinity crossed themselves and spoke darkly of old Tio Pedro’s superstition. Two Mexican women came forward. One told how on the morning of the killing she had watched several vaqueros pass her place en route to the post office. The other woman recalled seeing some vaqueros pass her house on the trail to Sonora. The latter declared their horses were heavily packed. Grim visaged ranchers from far and near snatched up their rifles and saddled their horses to search the border country for these merciless killers. During the following weeks all the hectic madness and frantic energy of the old frontier were present. Days in the saddle and nights beneath the stars were the order of the day. Cars were of practically no value in the search the country was too difficult and there were few roads. Posses rode over the parched desert and into the cool reaches of the mountain passes searching, searching. An airplane was chartered from the army post at Nogales to fly over this district in an attempt to get sight of the bandits. It was the first airplane ever used in Arizona for a manhunt.

Offer Bandit Reward A reward of $5,000 dead or alive was posted for each of the murderous-outlaws. This added zest to the quest. I had a hunch the men were safe in Mexico. Acting on this, White and I slipped away and crossed the line into Sonora where we conferred with the Mexican officials. Although there was still no extradition treaty between our countries these officials assured us of their fullest personal cooperation. True to their word, on September 6, 1921, Sheriff White received a communication from General Calles Plank, commander of the Mexican army in Sonora to the effect that his soldiers had forced two Mexican desperadoes out of a cantina where they had boasted of robbing the Ruby post office. Thankful for this hot tip, though we did not know who these desperadoes were, White, four deputies and I lost no time in getting to the designated place in the wild desolate country north of Saric, Sonora. We picked up tracks where two men had crossed the border into Arizona. The next two days found us winding in and around sage brush and up through the rough timbered Pina Blanca Mountains and across Bear Valley where, amid the bristling cholla and brown grease wood, shifting sands had obliterated all trace of our quarry. Again we returned to Nogales without our men. During the ensuing fall and winter months we ran down dozens of tips. Suspects were picked up on suspicion in Tucson, Los Angeles and El Paso. But they weren’t the men we sought “There’s one thing certain,” White declared as we later conferred on the case. “The men we are after may be hiding in the mountains of Sonora awaiting their chance to strike again. But while there’s still a chance that they’re on our side of the line we’ve got to keep after them.” By April, 1922, we had almost given up hope of ever apprehending the murderers, when there came a peculiar twist of fate. One of White’s deputies happened to be in a cantina in Sasabe, Sonora, a town thirty five miles southwest of Ruby. He was standing at the bar when he overheard the bartender bargaining with a customer. “Sell you all of them for three pesos? “No, I’ve only got two pesos.” “Guess I’ll keep them.” The deputy glanced around casually to see what was being sold. He paled when he saw five gold teeth lying on the counter. Five gold teeth, the same number that the murderous bandit had knocked from Myrtle Pearson’s pretty mouth! Gold teeth were rare among Mexicans. There was a possibility that this was a hot clue. “Where did you get these?” the deputy asked. “Oh, a feller by the name of Manuel Martinez sold them to me last fall. I had ‘em put away and just ran across them the other day and decided to sell them.” He grinned and leaned over confidentially: “I only paid sixty-five centavos for them.” Sixty-five cents Mex! The price of double murder! The deputy paid the astonished bartender his price and shuddered as he pocketed the teeth. After examining the teeth, White and I were positive that Martinez was the man we wanted. Here was a break at last. I had known Martinez by sight for years and also knew that his boon companion was a man named Placidio Silvas whose family lived in a shack in the Oro Blanco district. I saddled up my horse and poked over to the Silva’s place to pick up what information I could. I went alone so as not to arouse suspicion. Several months before I had questioned this same family, who were of the peon class, but they apparently had known nothing of the murder.

Trap One Suspect When I reached the Silva’s place, I noticed three horses saddled and tied outside. This indicated the presence of at least as many men inside. I chatted with a little girl and she told me Placidio was in the house. A bold course now scented wisest - to take them by surprise. I flung open the door and leveled my two six-shooters at the five occupants before they had time to realize what was up. I singled out Silvas, a brown-eyed, black-bearded youth. “You are coming with me to appear before Justice Maloney. You were in on that Pearson killing,” I told him. Silvas paled. “Caramba! I no do nothing bad.” “Ah mi hijo- my little boy,” his mother wailed. “If any of you try to stop me, I will kill Placidio,” and I slowly fingered my guns. It was a dramatic moment as I was alone and taking a dangerous man to jail from the bosom of his family. His two brothers were armed and glaring fiercely at me. I snapped handcuffs on his sturdy wrists, took all their guns, and edged out the door. Leading Silvas to his pony, I snagged his wrists to the saddle horn. I forced his brothers to unsaddle their horses and turn them out of the corral. To avoid the highway on the way back with my prisoner in order to forestall an ambush, so we took out across the silent wastelands and skirted the foothills, breaking our own trail. I glanced back frequently and listened carefully for sounds of pursuit. There were none and I got my man to Ruby late in the afternoon of April 29, 1922. “This is Placidio Silvas,” I told Maloney. “He is one of the bandits in on the Pearson killings.” “Smoke?” Maloney passed him a sack of tobacco and brown paper. Silvas deftly rolled a cigarette. Puff! Puff! He was perfectly calm. “Are you a Mexican citizen?” Maloney asked pointblank. Silvas looked up, surprised. He broke his cigarette in two and threw it on the floor grinding it with his booted heel. “I was born on this side, ‘way up in the Piña Blanca Mountains,” he answered. Maloney and I looked down at the cigarette butt and exchanged knowing glances. We took Silvas before The Mexican women who had declared they had seen vaqueros pass their places the morning of the Person killings. They identified Silvas as one of the vaqueros. He was charged with the murder of Frank Person in Santa Cruz County. Because he had so many friends of the outlaw class we turned him over to Sheriff Ben Daniels of Pima County for safekeeping. On May 10, the Oro Blanco ranchers and sombreroed men from Sonora packed the Santa Cruz superior court where Placidio Silvas went on trial for his life. I was in the court room listening to the evidence when I received a tip that Martinez was hiding in The Pina Blanca Mountains. I quietly selected a posse and slipped away. As I was thoroughly familiar with these mountains, I placed an ambushed guard at all the principal springs and passes and tried to pick up Martinez’ trail.

Strike Bandit Trail After two days in the saddle without results, I was poking along under the blazing sun and cursing our luck when the sound of rifle fire echoing through the hills jerked me to attention. I immediately started in the direction of the sound. I came across the fresh trail of a horseman in mad flight. I followed it and caught sight of my quarry just as he disappeared over a sharp bluff. He had also caught sight of me. The chase led down an arroyo which spread out into a valley. I was gaining on him when suddenly his horse stumbled and fell. He was thrown over the horse’s head. He got up and tried to run. It was Martinez! “Las manos arriba!” I commanded sharply. He stopped and complied, raising his hands slowly. I removed his heavy .45 and slipped on a pair of handcuffs. The injured pony in the meantime had struggled to his feet but was groaning in pain. I found he had stepped in a rut and broken his leg. Martinez, I know you were in on the Person killings and I aim to get your confession,” I told him grimly. His dark face flushed. “Why did you kill them?” “Quien sabe? ” he grunted with a characteristic Mexican shrug of the shoulders. “You will sabe pronto,” I challenged. Slipping my lariat around his neck, I tossed the other end over the limb of a cottonwood tree, tied it to the pommel and mounted my horse. My bluff worked. With a wild expression on his face my captive began uttering a flow of words, incoherent at first, which were to shock two countries. “Speak English,” I commanded. “I kill Senora Pearson for the teeth of gold.” And the man with the drooping mustache went on confessing how he and Silvas had divided the loot upon reaching their hideout in Sari, Sonora. Two of the posse rode up at this point and we fired six shots in rapid succession, the signal for the posse men to gather. We took turns riding double with Martinez until we reached the first ranch where we obtained a horse for him. The capture created quite a lot of excitement in Nogales. It was sensational as the Silvas jury had been out two hours. Martinez was immediately booked for the murder of Myrtle Pearson. Feeling ran high. Silvas’ counsel permitted the county attorney to call for the dismissal of the jury. The county attorney pushed the Martinez case because, for the moment, the evidence against him was more complete. I left immediately for Sari, Sonora, where the murderous desperadoes had divided their loot. I wanted to gather up the loose ends of the case to obtain some evidence to substantiate Martinez’s oral confession which I felt sure he would repudiate at the trial. I found the camp site where Martinez said it was. The most important evidence I found there was a book of money orders taken from the Ruby post office. This clinched the confession.

Guilty Of Murder On May 16. 1922, Martinez pleaded not guilty in the Santa Cruz county Superior Court, but there could be but one conclusion, because despite the defendant’s frantic denials and his numerous alibi witnesses, the state had the testimony of the two Mexican women and there was the horrible truth told by Irene and Elizabeth on the stand. On May 18, after deliberating only forty minutes. The twelve jurors found Martinez guilty of murder in the first degree without recommendation of mercy. That night I went to his cell in the presence of witnesses to get him to aid the prosecution in the Silvas trial which was scheduled to start the next morning. Although he had confessed to me that Silvas was his partner, he had since maintained a sullen silence as to the identity of his companion. “Silvas told me where you were hiding,” I began, hoping to start him talking. He shot a furtive glance ever his shoulder as though half’ expecting to meet the accusing eyes of one of those he murdered. “Why not tell us who was with you?” I urged. His black eyes snapped but he did not speak. I clung doggedly to the interrogation and finally aroused his anger when I continued to dwell upon the fact that Silvas had not attempted to help him. “Si,” he said finally, “We were together. We kill many gringos in the hills for their money. He recounted a list of their depredations along the Arizona border which amazed the county attorney. After he had finished he became calm and with a more satisfied look upon his face said, “Maybe now Dios will let me sleep.” The Silvas trial was started on May 19. The defense placed its strength in character and alibi witnesses. - Martinez’s testimony came like a bombshell. He declared that Silvas had been his partner in crime for several years, that he had always claimed his share of the loot and what was more important still that he had fired one of the shots at Pearson. The jury was unable to reach a decision. The balloting was reported to have shown eleven for conviction and one for acquittal from the very start. The jurors were dismissed and another trial ordered for Silvas. This third trial lasted twenty-one days and went on record as the longest criminal trial ever held in Santa Cruz County. After hours of battling, during which the ballots showed eleven for conviction and one for acquittal, Silvas was found guilty of murder, in the first degree with recommendation of mercy. On July 12, Martinez and Silvas appeared in the courtroom for sentencing. For their complicity in the Ruby post office atrocity, Martinez was sentenced to be hanged on August 18, 1922, while Silvas was sentenced to life imprisonment in the Arizona state penitentiary. “The crimes of which you have been convicted are perhaps the cruelest ever committed in Arizona,” said Judge W.A. O’Connor. “Let the punishment that awaits you serve as a warning to others who may contemplate the commission of similar crimes.” Judge O’Connor commended the work done by officers and citizens in this case and I was awarded $10,000 for bringing the desperadoes to justice.

Threaten Jail Delivery Now Martinez was a Mexican citizen and there was considerable feeling among his countrymen that he should not be executed by this country. Then there existed among some classes of uneducated peons a secret grudge held against all Americans based on the fear that the United States would ultimately conquer Mexico and place its people in servitude. By noon a group of friends of the convicted men had gathered in front of the county jail. As the day wore on the crowd grew, some of them cursing and muttering imprecations. Sheriff White realized an attempt at jail delivery would be made and, taking no chances of losing his prisoners, he sent for a detachment of U. S. troops from the post. With the appearance of the soldiers the crowd melted away and the situation immediately cleared. At eleven o’clock the next night White and Deputy L. A. Smith quietly loaded the prisoners into a touring car to take them to the state penitentiary at Florence. The late hour was chosen so as to forestall any possibility of an ambush. “Better come along, Oliver,” White invited. “No,” I replied, “I’ve got to get some sleep.” Noticing that my handcuffs were heavier than White’s, I suggested that he use mine. “Thanks. I’ll have the irons back to you tomorrow,” he said as he threw the car in gear and started north toward Tucson. Smith sat at his side. The two Mexicans were shackled together in the tonneau. “It’s raining,” I remarked to a newspaper man who was always on hand. “Yeah, and it’s the thirteenth of the month,” he replied ‘That’s so, and this is the last of the Ruby drama. “But it’s not over until Martinez is strung up,” he argued. There was no hint of tragedy on that nocturnal ride, yet the warm July rain that - pattered down on the car top beat a dirge of death. Br-r-r-rug. Br-r-r-rug. The telephone was ringing in the Tucson home of Ben Daniels, sheriff of Pima county and former Rough Rider with Theodore Roosevelt. Muttering to himself he glanced at his watch and saw that it was one o’clock in the morning. Whatever his thoughts were when he jerked the receiver down, they faded into oblivion when the speaker’s voice was recognized as that of his deputy, Dave Wilson. “Ben, I just got a call from Canoa Ranch that between there and Continental there’s a car in the ditch and probably trouble.” Daniels was wide awake now. “I’ll be right over,” he shot back, “Get Lou Tremaine, Carmen Mungia and Pat Sheehy and I’ll pick you up.”

Find Scene of Tragedy The deputies were standing in front he courthouse when Daniels pulled up. After a half-hour of bouncing over rough gravel roads, Daniels stopped abruptly. He and his men got out and went over to a wrecked car by the side of the road. They shuddered in horror at the spectacle revealed by the beam of a flashlight. Two bodies lay near each other, sprawled on the ground beside the overturned car. Daniels bent down to get a better view of the blood-covered faces. The features of the victims were distorted by expressions of horror. Their skulls were caved in. Daniels jerked erect and gasped in astonishment. “It’s Sheriff White and his deputy. Smith.” “Smith’s still breathing,” someone said. But White was dead, his left hand clutching a pair of handcuffs and his right lying over a .45 Colt. “This is no accident,” Daniels declared. “Those head wounds are the result of a beating. “Mungia, let’s get Smith to the hospital. The rest of you boys wait here. I’ll get the coroner and notify Nogales.” The shocking news of Sheriff White’s death was relayed to me and, hastily collecting a dozen deputies and a pair of trained dogs, I set out for the scene of the tragedy. We were a grimly determined group for we knew that Silvas and Martinez wire at large again. Two hundred feet from the wreck we found the place where the prisoners had jumped from the moving car. Nearby was a blood-stained wrench. We could visualize the crime. The Mexicans had a wrench-perhaps it had been cached in the car by some of their friends. The officers, believing their prisoners to be securely manacled, must have relaxed their vigilance. There was a short vicious swing with the heavy wrench and the sickening crunch of steel upon bone. White was reaching for his gun when he received the death blow. ‘While the car was still in motion the Mexicans leaped out and scrambled away. The car careened to the side of the road and turned over, throwing the two officers to the ground in the position they were found. The dogs would not take the scent. We believed this to be due to the rain which had long since stopped. There was nothing to do hut wait for daylight. The early light of dawn found us hot on the frail. The tracks told us that the men were still handcuffed together and that they were in full flight heading east toward Helvetia, - a deserted mining camp in the heart of the Santa Rita Mountains; we followed the trail for ten miles on foot before we obtained horses. Then the trail led over the mountains toward Ruby and we lost it.

Deputy Smith Dies Meanwhile, Deputy Smith died without regaining consciousness and as news of the third double murder spread through the country the rage of the people rose. Volunteer posses of officers and civilians poured into Continental from Pinal, Pima, Cochise, and Santa Cruz counties and they were detailed by Daniels to scour the desert and guard the roads. The warden of the state penitentiary brought the bloodhounds to the point where we had lost the trail, but they could not take the scent. For the second time dogs refused to help us! Harry Saxon, pioneer cattleman whose record as an officer and mountain tracker is without equal in Arizona’s history, was appointed sheriff to succeed White. He brought a large volunteer force of dry farmers and Indian scouts with him to join in the manhunt Five days after the escape there were seven hundred men enlisted on perhaps the most extensive manhunt in the history of the entire Southwest. There were five days of endless searching under the merciless desert sun! With the coming of evening, men gathered in groups and horses were hobbled to graze by members of sweaty, disgruntled posses. Saddles, saddle bags and blankets were dumped around the campfire. The smell of sizzling bacon and boiling coffee filled the air. A mellow crescent moon looked down. On the morning of the sixth day as the sun rose higher and higher in the sky, my men moved steadily south over drifting sand and through blistering wind. At high noon I met Harry Saxon. He was resting his horse in the shade by a deserted mine.

“Just picked this up” He handed me a blood-stained file. “They’ve cut the handcuffs, “I declared, “and they must be in this neighborhood? Saxon was tense as he rode along the canyon’s edge. Then in the foothills of the Tumacacori Mountains his horse suddenly snorted and kicked up his forelegs. Saxon looked curiously ahead. He could discern some object under a stunted oak. It was a bloody human foot! He shoved back the brush and peered closer. There lay Martinez and Silvas side by side raving with thirst and grown reckless with exhaustion! They had dodged from bush to bush over seventy miles of broken country filled with Spanish bayonet. An amazing feat of stamina and endurance.

The End of the Trail We flashed the word of Saxon’s find to the various posses and three hours later he and R.Q. Leatherman jogged into Nogales with the bruised and slobbering Martinez and Silvas. That night Saxon whisked his prisoners off to the penitentiary where Silvas was to spend the rest of his days and Martinez was to be hanged on August 18. But on August 18, Martinez was granted a last minute stay of execution so that his case could be reviewed by the state Supreme Court. This tribunal dismissed the case because of the delay in filing the appeal. The year 1922 dragged by and 1923 came in. Martinez had been held at the penitentiary during all this time. He was now returned to Nogales and Judge O’Connor sentenced him to be hanged on May 23, 1923. Martinez still had friends and relatives on the outside who worked unrelentingly for commutation of the death sentence. There was the formal intervention of President Alvero Obregon of Mexico who made a plea to Governor George W. P. Hunt to save Martinez because he was a Mexican citizen. This bold appeal gave the case an international aspect. But Governor Hunt and the Arizona Board of Pardons and Paroles refused clemency to the condemned man. Exactly twelve hours before execution time the attorneys representing Roberto Quiroz, Mexican Consul at Phoenix, obtained a writ of habeas corpus in Pinal County on the allegation that Martinez was to be executed without due process of law. The Supreme Court intervened, quashed the writ, and declared Pinal County in error. But the execution date had passed. Again Judge O’Connor sentenced Martinez to die on August 10, 1923. The gray dawn of Friday, August 10, came. Manuel Martinez knelt in silent prayer before a priest and received the last rites of his church. For the rest of Arizona that dawn gave promise of a bright sunny day but for Martinez it was the pay off for his murderous sallies in banditry. Warden R.S. Sims entered Martinez’s cell and touched him on the shoulder saying, “It is time.” Martinez heaved a deep sigh, stood erect, whipped off the gay bandana from his throat and walked down the corridor to stand squarely over trap. He was calm and collected, threw his shoulders hack, brushed his black mustachio and the black cap was slipped don over his head. The hemp noose was adjusted and the trap was sprung. Martinez was dead! He had paid his debt to society and finish was written to the Ruby post office enigma. Ruby, once drenched in blood1 stamped out the threat of bandit raids

by petitioning the U. S. War Department for protection. Today there

are mounted U. S. Customs officers and a deputy sheriff there. Prices

of metals have gone up and Ruby is again one of the liveliest mining

camps in the Southwest.

|

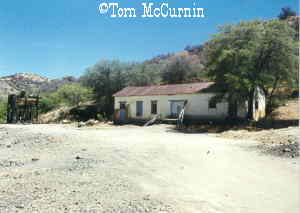

Headframe and Warehouse

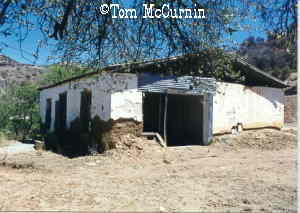

Equipment House

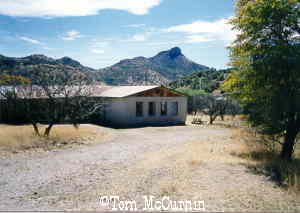

School

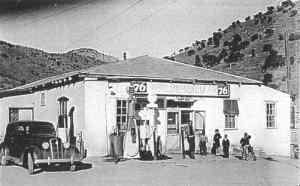

General Store - Late 1930's. Courtesy Tom McCurnin

Birdseye view - Late 1930's Courtesy Tom McCurnin

Ruby Courtesy Chuck Lawsen

|

|---|

|

|